A few weeks ago, city council candidate Dulce Vasquez posted a tweet about how she wished she could ticket cars that are parked in the bike lane, paired with a video of several vehicles parked in the bike lane, including a FedEx van.

The response to the tweet from certain people was… less than approving. Responses ranged from accusations that parking enforcement was akin to police violence, to requests that councilmembers focus on building more parking infrastructure, to personal attacks and insinuations that Vasquez didn’t understand what life was like for gig workers, and so on. The discourse around parking enforcement reached a boiling point when People’s City Council, a prominent police abolition activist group in Los Angeles, tweeted the following.

Despite how out of proportion the responses to Vasquez’s original tweet may have been, it makes some amount of sense — parking is one of if not the most contentious issues facing cities across the United States. Most NIMBYs oppose higher density housing in their neighborhood because they’re worried about the parking situation on the street should the building be built, as an example.

Parking disputes happened way, way long before some old homeowners got mad at the idea of an apartment building potentially jeopardizing their beautiful street parking spot. Donald Shoup, in The High Cost of Free Parking, discussed what is known as “the parking problem.” Namely, as car ownership grew in the 1910s and 20s, precious street parking spaces began rapidly disappearing as it became filled with cars. Since the parking meter hadn’t been invented until 1935, there was essentially no way to manage curb space for cars — congestion started to increase drastically and cities were stuck for a while.

Soon, however, some cities like Los Angeles came up with a solution that seemed to work at the time — namely, parking requirements. These rules would set a minimum number of mandatory off-street parking spaces based on a certain characteristic of a type of land use. Say, requiring 2 parking spaces per 1000 square foot of office space, or 1 parking space per hospital bed. At the time, parking requirements were considered ingenious — one mayor described them as “our greatest advance.”

However, as parking requirements and their respective parking spots proliferated, they drove a surge in car trips, to the point where over 85% of trips are made by car, while less than 2% are made by public transportation. The ways in which planners set parking requirements lead to several problems.

Planners in many cities often copy other cities’ badly designed parking requirements.

Many parking requirements are set based on arbitrary measures. A typical parking requirement for a restaurant might be set at 3 spaces per 1000 square foot of floor space, but square footage does not necessarily indicate parking space need. For example, a fast food joint will have higher turnover than a fancy sit-down restaurant, so in a freer market, the latter would probably purchase a site with more parking while the former would choose a site with less parking.

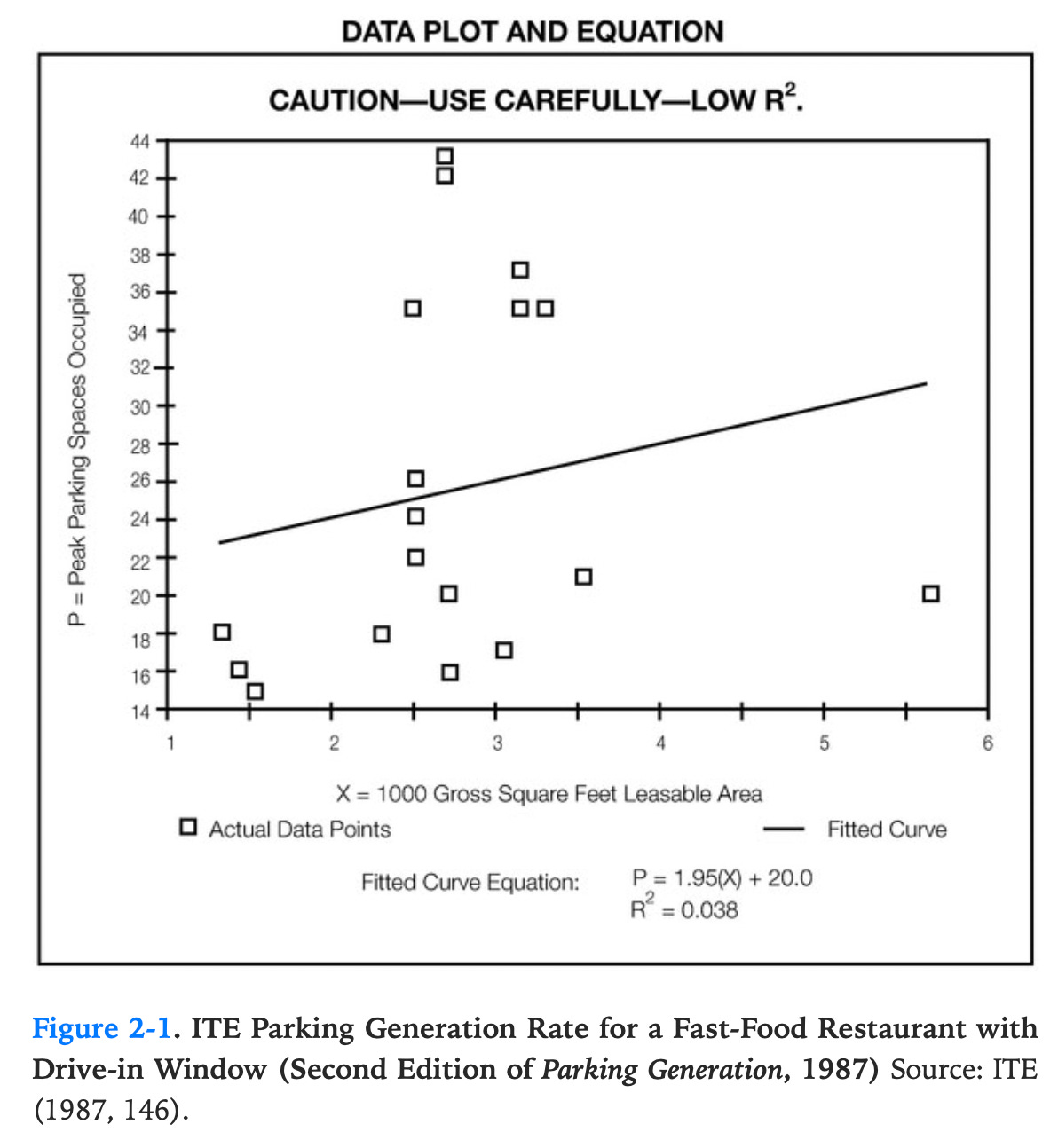

The planning method for parking requirements is very bad — the aim is to estimate the peak demand for free parking, which means basically nothing. A good like parking that is free at point of service does not carry a price signal with it, so no one really knows when to provide it, leading to groups like the Institute for Traffic Engineers (ITE) to publish manuals with graphs like this.

The method by which ITE data is generated results in an oversupply of parking, since it’s essentially impossible to model the demand for a good that is not priced. The consequences of such an oversupply are severe. For example, consider Apple’s campus in Cupertino.

Despite the fact that Apple planned to put a fair amount of green space in the area and that they have an intricate system of shuttles to transport employees such that about 30% of its employees don’t even drive to work, it was still mandated to build 11,000 parking spaces by the city of Cupertino, which totals to more than the area of the office building. (Those solar panel-covered pill shaped buildings at the bottom are the parking garages; each one is four stories, and the total area of the parking spaces in those garages is larger than the area of the entire campus.)

Apple may be a trillion-dollar company, but many of those parking spots that they were forced to build will remain unused, and they will most likely have to pass on the cost to the customers — a very small part of the cost when you bought your iPhone or MacBook was for the parking in those very structures.

The economist’s motto of “There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch” (TANSTAAFL) applies to parking just as it does to everything else. When someone parks for free, the price that they would have paid for parking does not disappear, it merely gets applied to different transactions, such as the rent a tenant pays or the price of food at a restaurant. In essence, “free” parking is not free, it is just paid in the cost of other things, and so represents a net transfer of resources from non-car owners (who buy groceries and pay rent that includes the price of parking) to car owners (who do the same, but also receive the subsidy from parking free).

Thanks to the abundance of parking, there are about 3 free-at-point-of-service parking spaces for every car, which for an average cost per parking space of $4000 per space, summed up to more than the total value of cars in the United States. In 1991, the total parking subsidy — the cost of all the parking in a year less the amount per year paid for parking — was about $76 billion at the lower end, and up to $225 billion at the higher end. Adjusted for inflation, that would be between $140 billion on the low end and $414 billion on the high end.

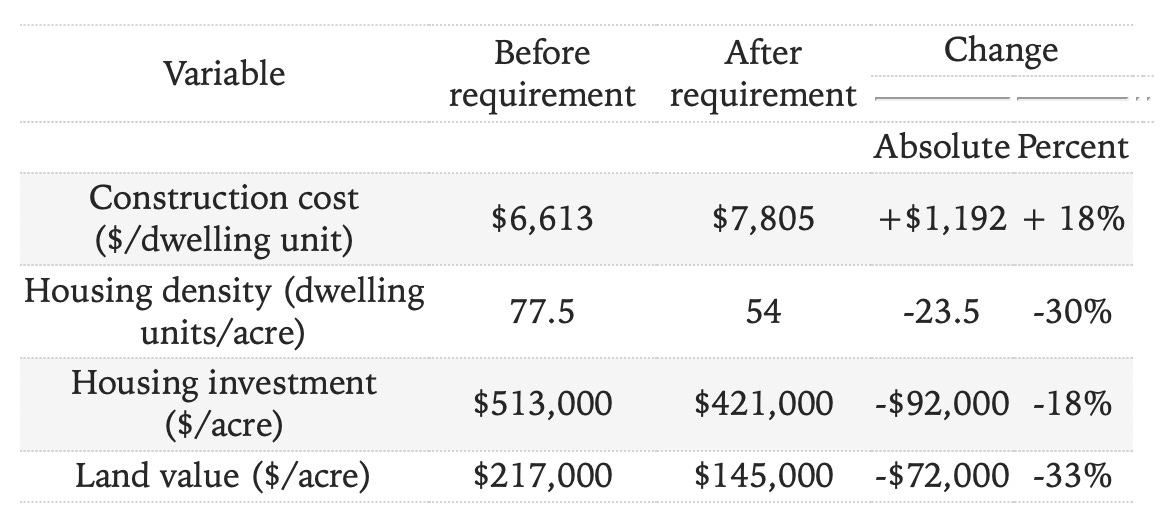

This parking does not just get absorbed into the cost of everything, it also defaces the urban landscape, and reduces the utility of land. As seen in the table below, the value of land per acre in Oakland, CA, dropped by 33% after the institution of a mandate — since the value of land is related to its ability to be used by the Law of Rent, it’s pretty clear that mandating parking, in this scenario at the very least, reduces the utility of each parcel of land, preventing it from being brought to better use.

The parking lots that litter the landscape of cities like Los Angeles and San Jose make life for pedestrians and cyclists harsh by spreading out destinations far beyond walking or cycling distance, and meanwhile leading to more vehicle trips that pollute the air for those pedestrians and cyclists. In addition, those vehicle trips increase traffic, which buses get caught in, making the bus a less attractive option than cars, thereby increasing car traffic in a vicious cycle.

In addition to the perils of mandatory off-street parking, there is the matter of street parking (or curb parking) that is also free at point of service despite its limited supply. In essence, free street parking is a common good — it is rival (someone else using a parking spot means that you cannot use that spot) and non-excludable (no one is charging a price for the street parking).

When street parking is free or underpriced, drivers will cruise around in an attempt to nab a spot. Especially in high demand areas like the central business district, cruising for street parking makes for a surprisingly high proportion of traffic in the area. Additionally, cruising is worse than other forms of traffic since cars are going slow, stopping a lot, and therefore polluting a lot more than they would be if they were going at full speed.

The problem of cruising for parking is a hidden cost of street parking — just as the cost of subsidized housing is not only in the rent but in the form of a waitlist, the cost of “free” street parking is not in the price of the parking itself, but in the “price” of cruising around to find a street parking spot.

Dealing with and reducing the costs of free parking (defaced urban landscapes, excessive driving, pollution, etc.) is something any serious urban reformer must grapple with. Donald Shoup, in the book, proposes three solutions to help reduce the costs of free parking and help rebalance the deck in favor of more favorable transportation alternatives:

Charge “the right price” for street parking.

Return revenue from street parking to the blocks that are metered.

Remove all parking minimums.

Let’s go over each one of these ideas.

To start, it’s important to note that, since street parking is a common good, it will almost always deal with a corresponding “commons problem” (described by the Malthusian ecologist Garrett Hardin in a 1968 paper in Science), namely that without some form of management, free street parking will be subject to overuse and misallocation.

To solve this, Shoup proposes using performance pricing on parking meters in order to deal with demand. In essence, the meters should adjust their prices until a target has been met (namely, about one to two spaces open per block). This idea has multiple advantages over the current system:

By tying prices to a target instead of requiring typical city government channels to change parking meter prices, meter rates no longer become political decisions.

The performance target makes it so no driver will perceive that there is a “shortage” of street parking, since every block will have a couple open spaces, the driver will be able to pull in, pay, and pull out without complaining about the lack of parking.

By preventing cruising through performance pricing, the scheme is able to make the air cleaner and reduce traffic congestion caused by cruising.

The performance pricing system is applicable to many other situations. For example, in a piece for Bloomberg CityLab, Shoup advocated using performance targets on tolled roads in order to keep a free flow of traffic. The revenue from congestion pricing in the LA area could measure in the hundreds of millions for just the downtown cordon.

Next, in order to sell the performance parking scheme, Shoup proposes creating so-called parking benefit districts in the various business districts within a city, and earmarking the district’s meter revenue for public services within the metered districts.

The prime example of such a parking benefit district is Old Pasadena, whose parking district was established in the 1990s to induce parking space turnover and bring more customers to the neighborhood. Before the installation of the meters, the area now known as Old Pasadena was a backwater moribund district, with shops in decay. The parking meter revenue is dedicated to, among other things, street sweeping, horse and foot patrols, tree coverings, and steam cleanings.

According to the mayor of Pasadena at the time, Old Pasadena’s merchants were not sold on the idea of adding the meters because they were afraid of scaring away all the customers to their business. However, when he brought up the idea of spending all the meter revenue on public services within Old Pasadena (as opposed to putting all the revenue in the general fund), the merchants were sold.

If one goes to Old Pasadena today, they’ll see that it’s an extremely beautiful place. The streets are clean, sidewalks wide and high quality (as opposed to the broken sidewalks that litter the neighborhoods of Los Angeles), and there are tons of businesses small and large throughout the district. The parking meters in Old Pasadena generated around $1.5 million per year before the pandemic, and sales tax revenue in Old Pas grew at a faster rate than other business districts.

Inherent in the need for paid street parking is the need for parking enforcement, and this is where urbanist disagreement with police abolitionists came to a head back in January. As for my personal views, I believe that, among the deterrents of severity (how high the fines are) and certainty (how certain a driver is to get fined), certainty has a much larger role to play in dealing with non-payment at the meter. The current system of spotty parking enforcement with high fines doesn’t seem to deter drivers from parking in the bike lane or not paying fully at the meter, at least in Los Angeles.

Donald Shoup, ever the sage, noted that parking fines tend not to be focused on deterrence, but rather nearly entirely on budgetary concerns. Structural reforms to tax codes aside, the point of parking fines should not be to raise revenue, but rather to disincentivize bad behavior on the part of drivers.

Darrell Owens has a much more in depth analysis of parking enforcement, and I highly recommend reading his take on the idea.

Finally, the last and perhaps most impactful reform of them all is to remove all mandatory parking minimums. A study from the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in Canada found that an additional mandated parking space per housing unit increased the cost by 12.5%, meaning that removing said parking minimums and allowing developers to build less parking reduces rents by up to 20%.

Improving housing affordability and parking management doesn’t just come in the form of allowing developers to build less parking, but also by allowing condos and apartments to “unbundle” the parking cost from the cost of the building. In essence, allow condos and apartments to charge residents for when they do store their cars, rather than charging all the residents higher rents and allowing them to park free. Unbundling provides two main benefits: it reduces rents for people who do not own cars, and it provides a disincentive to excessive car ownership.

Shoup notes that, assuming an elasticity of VMT with respect to fixed costs at -0.5, there would be a 90% annual reduction in vehicle miles traveled for the median car assuming a parking price of $150/month per spot. The most inefficient cars (namely, older second, third, and fourth cars) are heavily disincentivized in an unbundled parking regime, since they have the highest % increase in costs when parking is unbundled. Essentially, under an unbundled parking regime, there will be fewer cars on the road, and the remaining cars will be more efficient new cars.

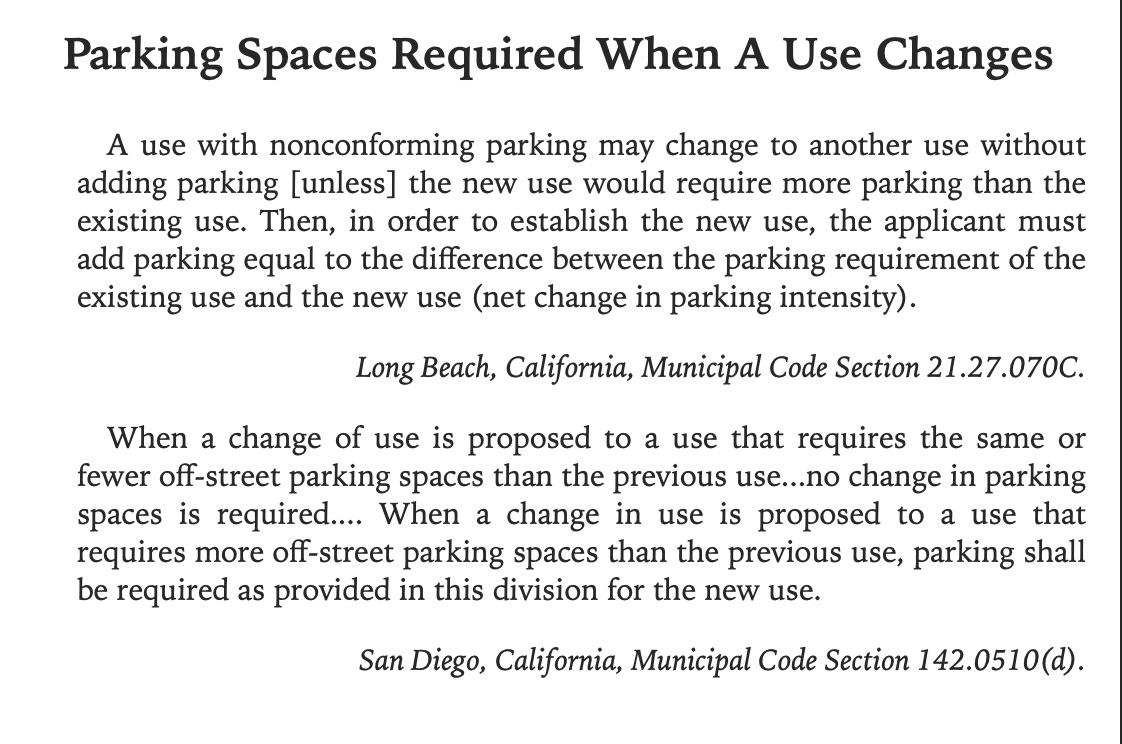

In addition to the effects on housing costs and vehicle miles traveled, removing parking minimums creates walkable urban spaces. By reducing the number of curb cuts (conflict points between cars and pedestrians), pedestrians are more willing to visit shops and explore the neighborhood. In addition, by removing the need to build new parking when changing land use (as is currently the case in most California cities), repealing parking minimums facilitates business churn necessary for a vibrant pedestrian district.

An example of the success of removing parking minimums can be found in Los Angeles’s 1999 Adaptive Reuse Ordinance (ARO). Before the ARO, housing conversions from other uses would require two parking spaces per apartment, which led to the abandonment of many downtown LA office buildings, as builders were unable to satisfy the demand for apartment conversions since they would be mandated to demolish many of the buildings to provide free parking.

The ARO changed the dynamic, though, as it no longer mandated that conversions of old office buildings to housing require parking (and included other things like expedited approval). What happened post-ARO was a veritable resurrection of downtown LA — before, the area was a moribund backwater like Old Pasadena was before the parking meters. By expediting approval of office to housing conversion, and no longer mandating parking, the ARO opened up opportunities for cheaper housing in a dense area with lots of transit connections, without mandating large parking lots of expensive parking garages.

As Darrell Owens says in his great piece on banning cars, it’s perhaps better to, rather than manipulate the cars themselves, manipulate the built environment that cars specifically rely on, and use the built environment to create a car-free future. Where better to start than parking, that most invisible yet most powerful force that shapes our city design? To start, let’s adopt Donald Shoup’s proposed reforms.

Charge market prices for street parking, enough such that there are one to two spaces open on every block.

Return all the parking meter revenue to the specific districts that have the meters.

Remove all mandatory parking minimums.

By rebalancing the built environment away from its massive skew towards cars, we will go quite a ways towards the ideal of few (if any) cars, and more walking, cycling, and public transportation.

Save road space. Park cars owned by residents away from the residence so that the space around the home is a safer place for kids to play. Walk from the garage to the residence and meet ones neighbours as one walks. Why not? No street out front means no parking problem. Add cafe, meet neighbours over a cup of coffee.

The photo captioned "The typical urban landscape in Los Angeles" is an argument FOR parking lots, apparently we need very large parking lots maybe even more of them.