Most of the states in the United States depends on revenue from a multitude of sources. For example, in my home state of California, we raise revenue from:

Property taxes (from residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural uses)

State Income Tax (which includes dividends, business income, and capital gains)

Sales Tax and other forms of consumption tax (like vehicle licensing fees)

Corporate Income Tax

These four types of taxes are common throughout most of the states — some states like Washington will not levy an income tax and instead will levy higher property and sales taxes, while others do not have sales tax like Oregon.

The problem with these classes of taxes is that they also create deadweight loss (loss of economic activity). If you tax income, people will have less to spend and invest in the economy, if you tax capital, businesses will invest less, and if you tax buildings, you will disincentivize improvements — another form of productive investment. Generally, productive investment is a good thing, and the fact that our tax system disincentivizes productivity and investment is less than ideal — in a perfect world, we would not need to tax production for government revenue.

You might think that there is no way to raise public revenue without taxes on production — after all, where will the money come from? However, there are sources of revenue that are all around us — in the air and beneath our feet.

Henry George’s Progress and Poverty was far from the first book to propose a tax on land value — the idea goes back to Adam Smith. However, Progress and Poverty attempted to identify the fundamental problem with progress — why, with so many technological advancements, from the steam engine to electric light, was poverty so persistent?

Let’s first start with an examination of wages and capital from Progress and Poverty, by first asking the question posited in Book 1:

Why, in spite of increase in productive power, do wages tend to a minimum which will give but a bare living?

The common explanation at the time was that wages were drawn from “capital” (we’ll discuss what capital means later), and that as the population of workers grew, capital remained scarce so people’s wages tend to a minimum. This explanation is false.

George noted that interest (the return on capital) is high when it is scarce, so it would make sense that high return on capital would be associated with low wages, and low return on capital would be associated with high wages (as workers would be supposedly be able to draw upon more capital and have increased pay, and vice versa). This wasn’t borne out by the conditions at the time — George noted that both interest and wages were higher in the United States, for example, and that interest and wages in western states (which were at nascent stages of development at the time) were higher than those in eastern states.

So, what exactly is the source of wages if capital is not their source. George posited the following:

That wages, instead of being drawn from capital, are in reality drawn from the product of the labor for which they are paid.

In essence, workers create wealth and some of that wealth goes back into their wages. This idea is pretty similar to the theory that workers get paid their marginal revenue product in contrast to the Labor Theory of Value, the prevailing theory at the time.

Before going any further, let’s discuss what wealth actually is. Wealth is the result of human exertion applied to natural resources, and it is tangible. For example, a cobbler who turns leather into shoes creates wealth, and the shoes are the cobbler’s wages, according to George. Money, stocks, titles to land, and so on are not wealth — in the case of the cobbler it is the shoes they create that are the wages, not the money received from selling those shoes.

Now, consider that the cobbler puts some of their earnings towards a new set of scissors that reduces the time to make a pair of shoes from leather. The scissors is capital — defined as “that part of a man’s stock which he expects to afford him a revenue” by Adam Smith, or more succinctly as “wealth that is dedicated to creating more wealth.” Since these scissors were created by a person, and are used in production, it’s pretty clear that the cobbler’s increase in productivity from using those scissors isn’t drawn from capital, but rather capital (the scissors) is a factor in producing the shoes, not the source of the cobbler’s wages.

It’s important to note here that capital is not only a factor in production, but is wealth and so is the result of production — basically, anything that isn’t produced but still gives people wealth is not capital. This is where land comes in — land is not just the parcel you own, but is all natural resources such as oil, air, groundwater, and so on.

The return from land is called rent — this “land rent” is similar to but slightly different from the rent a tenant pays the landlord. Some of that “contract rent” is made up of the land rent and some is return from capital and labor that the building owner put into renovations, building the very building, and so on.

Land rent is economic rent (returns in excess of the cost to bring a factor into production). Since land has no cost to bring into production — natural resources existed long before anyone decided to use them — any value that land holds is monopolized solely by person who holds title over the land. These features are also augmented by the fact that the rent of land is a drag on both capital and labor. Henry George illustrates this using algebra. Let “Produce” signify all the wealth that is in the economy:

produce = wages + interest + rent

The reason we include “rent” in produce is that both capital and labor pay rent to landlords from their production. With a simple rearrangement, we get the following.

produce - rent = wages + interest

Since wages and interest reflect labor and capital (which actually create wealth), this equation shows that the wages and interest from the produce labor and capital create are depressed due to the rent that each must pay to the landowner.

Worst of all, rent is the factor of production that grows in value as society becomes more advanced. Consider the three general types of progress that a society experiences: population growth, technological advancement, and an increase in social capital and the general quality of life.

As the population of a society grows, firms and the economy generally become far more productive, as the division of labor and specialization make it so 100 workers can do far more than 10x the work of 10 workers. The comparative advantage of a piece of land becomes higher due to this increased productivity, and since the comparative advantage of land is equal to its rent by Ricardo’s Law of Rent, the landowner is able to extract more rent out of tenants due to population growth.

As technology advances, just as with population growth, workers are able to be more productive on the same piece of land. The comparative advantage of a piece of land goes up due to this increased productivity, and so the landowners are able to charge a higher rent for it.

Finally, as social capital in a community increases, people in the community become more happy and productive, and demand to live in such a community increases for the same amount of land — therefore, the value of land also increases in this scenario.

However, there is a solution to this madness. We don’t have to see that as society advances, so do land values and poverty with them.

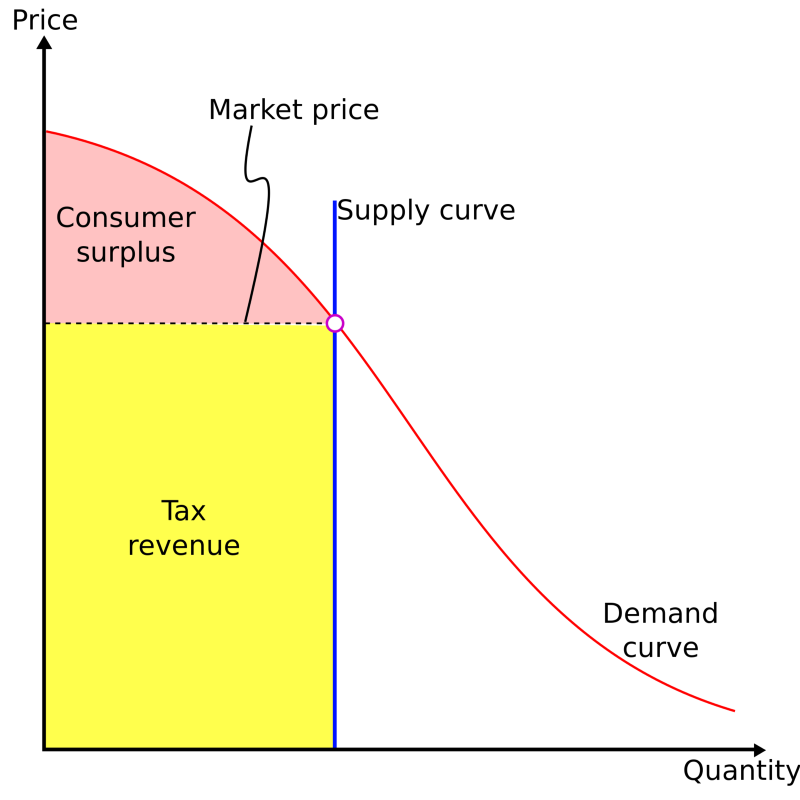

Since land has a perfectly inelastic supply curve (since you cannot create more of it), yet it still has value, we can tax it with no deadweight loss. Even at close to 100% there is no deadweight loss to land value taxation.

The advantages of land value taxation are numerous:

It is a progressive tax — the richest people own the most valuable land, and so have the most ability to use it in an economically efficient manner so as to pay the land tax.

Like said previously, it has little to no deadweight loss.

It encourages sufficient stewardship of valuable land — surface parking lots in San Francisco would be no more under a land value tax.

Since, under a proper land value tax, improvements such as buildings would not be taxed, meaning that a tax on land would incentivize improving buildings that would otherwise fall into disrepair.

The incidence of the land tax falls squarely on the landlord, who does not contribute to the economy unlike the capitalist or worker.

As for the last point, you might be wondering why the tax on land falls on the landowner entirely. When it comes to other taxes on the producer of a good (such as a Value Added Tax or VAT), the company can restrict the supply of the good and pass on some of the tax to the consumer. The incidence of a value added tax falls partially on consumers (through higher prices) and partially on producers (through lower return from sale).

The landowner rents at the price that the market will bear — essentially, the tenant is paying the maximum price that the landowner can set, and if the landlord raises the rent any higher, the tenant would move to a different landlord who sets rent near the market price. In the words of Adam Smith, “Rent… is naturally the highest which the tenant can afford to pay in the actual circumstances of the land.”

Now, suppose, we implement a tax on land — the landlord can try to raise the rent that the tenant pays, but rents reflect the value of land, and so would be paying more in taxes anyway. This means that the landowner holds the entirety of the tax burden, and none of it falls on the consumer/tenant.

We can see this through the graph of the land tax — there is still a consumer surplus no matter whether the tax is at 1% of the land rent or 100% of the land rent, meaning that the tenant does not bear any of the tax.

The ideal of a land tax is that it would be a single tax — in that taxes on land rents would replace tariffs, excise taxes, personal income taxes, etc. You might ask whether this would raise enough revenue to fund the government, because after all the federal government gets around 4–5 trillion dollars in tax receipts per year, and spends 5–7 trillion. Where would we be able to get all this revenue from just land and other natural resources?

First, we need to understand that, at the moment, we don’t really have proper data to know the revenue that can be gained from land at the current moment. Georgist economist Mason Gaffney noted that there are many problems with the current system of tax reporting and assessments that make the current revenue potential of land more obscured, including but not limited to:

Assessed value of land generally lags behind the actual growth in land values — in some cases the assessed value is way below the actual value, as in the case of California’s Prop 13.

Zoning laws artificially distort the actual value that can be extracted from the land.

Homestead exemptions

Assessing the building first rather than the land

In addition, Gaffney noted that IRS data is very distortionary on what the actual level of land rent is in the economy, primarily due to current depreciation rules that lead to landlords reporting little to no taxable rent, and since the “total rent” in the US is the sum of the reported taxable rents, IRS data implies that there is way less taxable rent than there actually is. This is in addition to the fact that the IRS does not calculate imputed rent (rent that’s captured by a homeowner on the land that they own and live on).

Gaffney proposes some policies that use the expansive definition of land (all natural resources) to propose variable fees (as opposed to fixed rates) that can capture the value of natural resources for common good. These include:

extraction fees/severance taxes on groundwater, oil, natural gas, and so on

market prices on street parking (one of the policies proposed by Donald Shoup in his book The High Cost of Free Parking)

congestion pricing on arterial roads (recently proposed in New York City)

pollution pricing (on methane, sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide, etc.)

All of these are very good policies regardless of their place in the Georgist tradition, as they serve ends that preserve the environment and prevent wasteful overuse of public space such as roads and natural resources such as water.

We can also use current tax law to raise revenue for the government from the land.

Let’s start with the 16th amendment, which was pushed by Georgists in Congress as a way to reduce the United States’s reliance on tariffs (perhaps the worst type of tax in terms of its negative effects on the economy).

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration. (emphasis mine)

Before the 16th amendment, “direct taxes” had to be “apportioned” based on a state’s population — as in, if California had 1/8 of the country’s population, taxes directly on the populace had to yield 1/8 of the federal government’s tax revenue. (Direct taxes are taxes paid by individuals directly to the federal government rather than paying for them through goods and services, which are indirect taxes.) The apportionment clause in effect only allowed for head taxes or capitations (a set dollar amount paid by every person in a state) as the only form of direct taxation.

Most importantly, the phrase “from whatever source derived” in the 16th amendment allows for taxation from property income (basically, land taxation). Gaffney’s proposal is twofold: first, exempt wages and salaries from income taxation, as had been done for the first years of the income tax’s history, and second, implement full expensing on all corporate investments.

The way companies work right now is that if they undertake any capital investment (say, buying a robot in a factory), when they file their taxes they have to “depreciate” the investment according to rigid schedules (of which there are a lot). This makes the tax code a net negative towards investment — the corporation doesn’t have the ability to reflect the cost of the investment in their taxes. Full expensing solves this by allowing the corporation to deduct the full cost of the new investment in the first year that it is made.

One of the (many) upsides of full expensing is that it prevents depreciation of land (which is illegal but still happens), since there is no depreciation on old buildings as companies would have expensed them.

The benefits that can be begot from land value taxes are enormous — reducing or even eliminating poverty, more dynamic and productive urban centers, lower housing costs and rents, more mobility for regular people, climate resilience, and so on. Sadly, though, we may not be able to achieve the full land value taxation that we so desire. However, there are a few action items that Georgists can work towards implementing at this moment in time:

Zoning reform, allowing more housing to be built and creating a base of renters who would be amenable to Georgist policy that materially benefits their interests.

Property tax restructuring, such as Prop 13 reform in California (the failed Prop 15 in 2020 was a good starting point). Examples include advocating for split rate tax that reduces taxes on buildings, assessing land values first rather than calculating land values from buildings, proper public access to assessment information, and so on.

A basic income or citizen’s dividend — the idea of a basic income from the value of land was promoted by, among others, Thomas Paine, Thomas Spence, and Henry George himself. Providing a basic level of cash support to everyone is a crucial part of alleviating poverty (which is among the end goals of Georgism).

Pricing the commons, such as market-based street parking metering, congestion fees, market pricing water extraction, carbon taxation, and so on.

Turning government privileges such as patents, rights to the radio spectrum, oil extraction rights, and so on into consistent revenue streams by, for example, implementing a Harberger tax, or in the case of the radio spectrum changing from auctions that lead to sales to auctions that lead to leases.

Corporate tax reform that incentivizes investment (such as full expensing) while ensuring proper taxation of the rents that corporations otherwise may accrue.

A more equitable and just system to raise revenue while increasing productive capacity in our economy is possible. A tax system that acknowledges our collective right to the fruits of nature, rather than any one individual.