Is housing popular? Does it matter?

My thoughts on pro-housing electoralism

On occasion, there is a discourse on Twitter along the lines of the following:

YIMBYism is electorally unpopular.

Of course, I’m not going to dispute the cases where a pro-housing referendum has gone down in flames. To give some credence to this argument, I’m going to give some examples from the far past and more recent present.

A ballot initiative to lift a conservation easement to allow a housing development on a shuttered golf course in Denver failed 59–41 in April.

In 1986, Los Angeles passed Proposition U, which greatly restricts new housing development in the city by restricting allowable floor area.

In Boulder, a measure to ease the restriction on allowable residents in a house was not passed.

Many of the endorsements local YIMBY group Abundant Housing LA made in the city council primaries did not get to the general (which I am pretty sad about)

Alex Fisch, pro-housing councilmember extraordinaire in Culver City, was defeated.

However, I am going to posit that, even with these results in mind, pro-housing electoralism is still a viable position — and so is pro-housing technocracy.

How (local) elections fail

Of course, it’s important to note that those aforementioned electoral failures of YIMBYism were all in local elections. This context can explain why many people on election Twitter view pro-housing policies as electorally unpopular.

The more local the context, the more pro-housing policy becomes distasteful to electorates. This is pretty obvious: the perceived negative externalities of new housing, primarily their effect on local street parking and traffic, are more felt when you live right next to the new housing project, while the benefits such as lower rent are more diffuse. If you went to the YIMBYest of YIMBY constituencies in California, they would probably still vote against a new apartment building in their neighborhood.

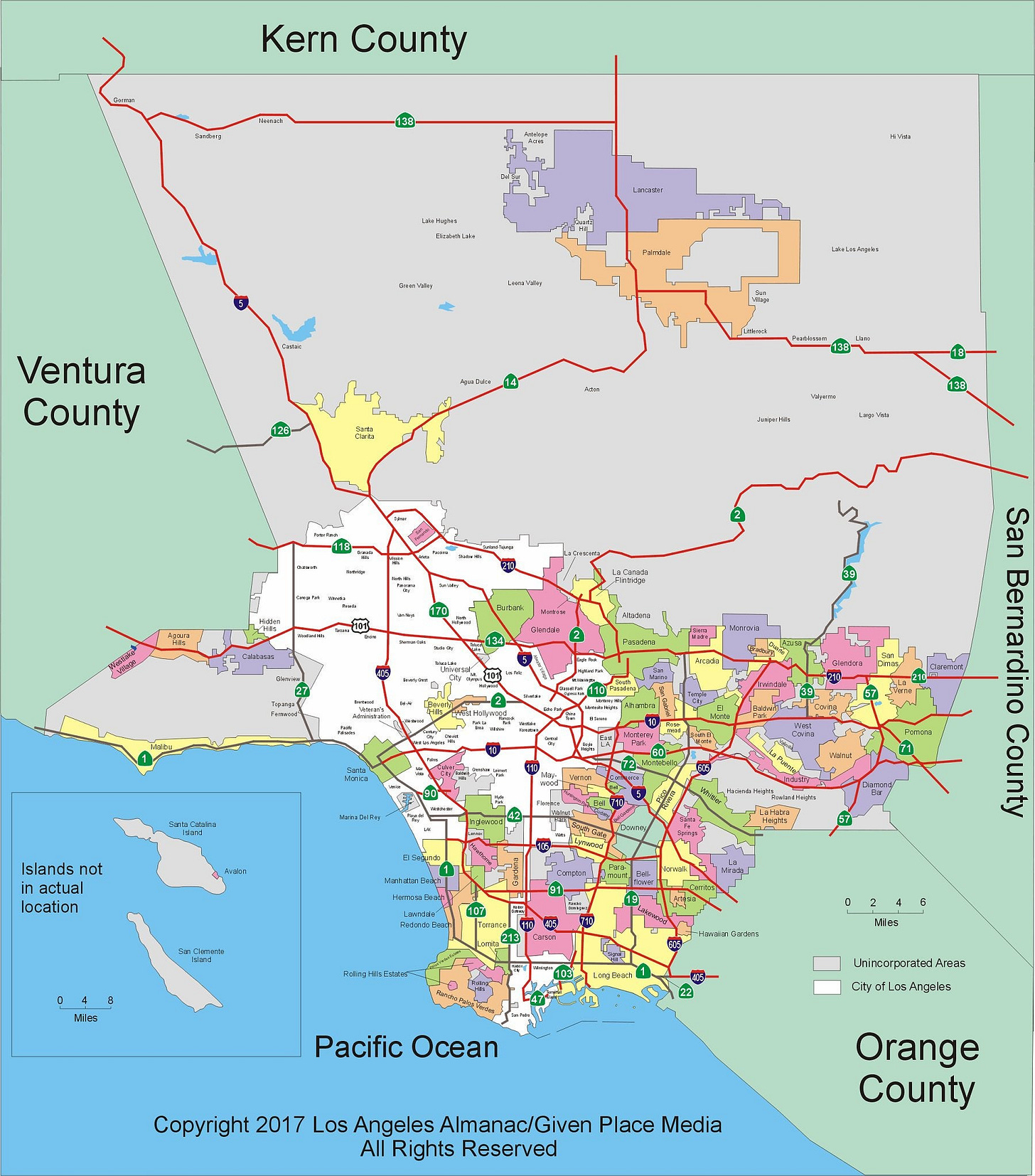

Fundamentally, when your metro area is balkanized into dozens or hundreds of jurisdictions, it is impossible to internalize the positive externalities of new housing construction. In Los Angeles, this is made further by councilmember prerogative — effectively splitting the city into 15 subcities, each controlled by the councilmember — and the community plans, which split the city into 35 more subcities.

So, what is the solution, seeing as local democracy will necessarily fail?

How (state) elections succeed

In the leadup to the 2022 primary, a barrage of weird election mailers hit households in AD-24, implying that the local assembly member, Alex Lee, was “soft on crime.”

If you look at the bottom right corner of the first advertisement, you’ll see that this advertisement was paid for by the California Apartment Association and California Association of Realtors, two landlord lobbying groups, targeting Alex Lee for his support for new housing and tenant protections.

In total, the group spent over $1 million in independent expenditures against Alex Lee, but not only did he not lose his primary, he didn’t even have to face a Democrat in the general election.

Other statewide pro-housing legislators, such as Scott Wiener and Buffy Wicks, sailed to their reelection in 2020 and 2022 respectively, despite the former representing San Francisco and the latter Berkeley.

In this, we can see how pro-housing politics has won in California. They exclusively focus on state housing legislation. The activation energy for the lean-NIMBY median voter to call in opposition to a state bill promoting new housing is much higher than for them to vote against building an apartment building 2 miles down the road.

I’m not going to go all the way to say that housing is popular — again, local elections that are yes-or-no votes on housing generally lean no — but local elections that are yes-or-no votes on housing aren’t how zoning will get liberalized.

In addition to the energy required to oppose state housing laws, the state housing laws themselves are very technical. Some of the most impactful ones, such as SB 35 and SB 330, deal with ministerial approval, entitlement application rules, and no net loss provisions, things that very few people can informatively talk about.1

Does Popularity Matter?

In addition to the fact that there is an opening for pro-housing politics, particularly at the regional and state level, there are also the question of issue salience and status quo bias.

Generally speaking, a lot of people don’t really care about the nitty gritty of housing policy. They may be opposed to one particular apartment building, but in my experience when you tell people that they aren’t allowed to replace their house with a duplex or apartment building, they will be confused or shocked. There usually is not a lot of popular understanding about the implications of housing policy, which implies greater leeway on the part of local and state elected officials to create pro-housing politics without worrying about electoral backlash.

In addition, status quo bias rules a lot of thinking regarding housing — there might be a lot of anger about a proposed apartment building, and people will probably vote against it, but once it’s built, few if any will care. Though this is a greater hurdle than issue salience, what it shows is that policy-wise, moving fast and defanging the most vocal NIMBYs (such as through ministerial approval and state housing laws) will probably yield dividends both in lower housing costs and very limited electoral impact.

This is why I am not particularly concerned about the long run effect of the poison pills contained within SB 9. Bills to remove poison pills are much more technical in nature, and so fewer people will be able to talk about them in a way that leads to the bill’s failure.