Why is the Los Angeles City Council so corrupt?

Why does this keep happening?

Background

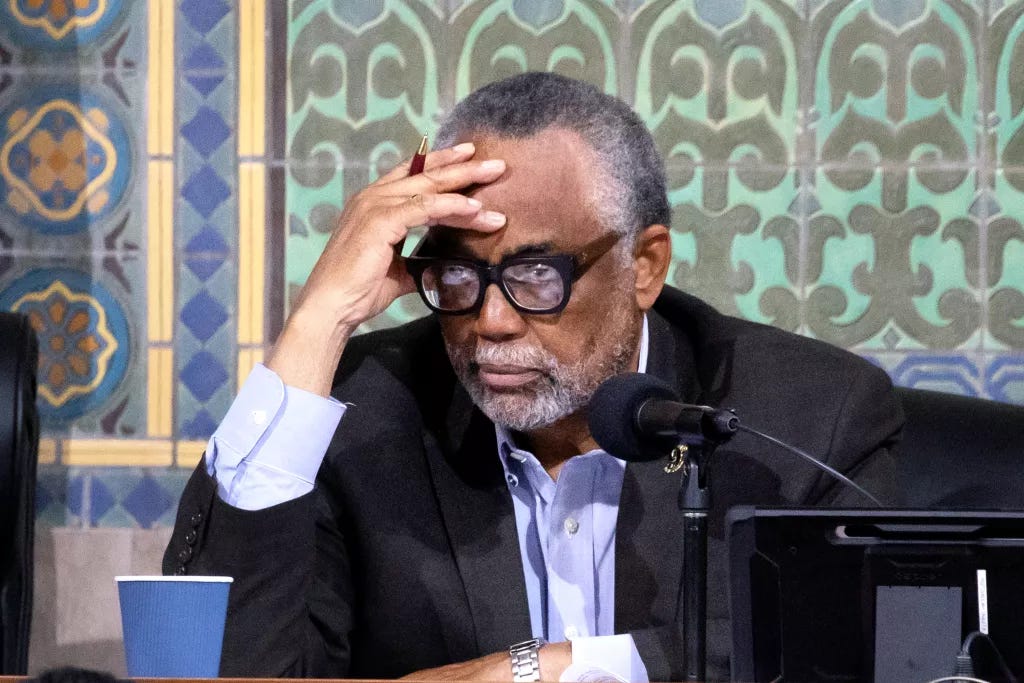

On June 13, Curren Price, member of the Los Angeles City Council for District 9, was charged with embezzlement, perjury, and conflicts of interest, primarily relating to a series of housing development applications that his spouse consulted on from 2019–2021.

Of course, this is not the first, or second, or even third time that a councilmember has been caught up in a corruption scandal in recent years. In 2021, Mark Ridley-Thomas was suspended after he was charged with misusing his position on the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors for personal benefit. In early 2020, Mitchell Englander was charged with accepting bribes in 2017 from a Los Angeles businessman; he pleaded guilty in 2020. Similarly, Jose Huizar pleaded guilty to corruption charges stemming from soliciting bribes from real estate developers during his time in office.

So, what’s going on here? Why is Los Angeles so corrupt? Will this end anytime soon?

The Corruption Equation

Courtesy of the Twitter user HeadwaysMatter, the equation that helps explain corruption is the following:

corruption = discretion + monopoly - accountability

As we will see, the governance system in Los Angeles — and especially the land use governance system — satisfies virtually all of these conditions. What led Curren Price, Mitchell Englander, and Jose Huizar to take bribes from real estate developers will continue to happen so long as this system of land use governance remains firmly in place.

Discretion

In Los Angeles, many housing developments must receive the blessing of the local councilmember before it may commence construction. You might ask:

But aren’t zoning rules or general plans supposed to lay out by-right rules?

In regular cities, this is theoretically the case. However, in Los Angeles, the zoning code and general plan have been so discordant at many points that virtually any housing development must go through a zoning change or general plan amendment. In many cases, the existing use would not conform to the zoning!

Zoning changes go through the city council. And, when every development requires a zoning change or general plan amendment, this means the council has immense power over the fate of the development. By custom, the councilmember whose district the development is in is deferred to with regards to the acceptance or rejection of the zoning change.

Defenders of the system argue that it allows councilmembers to extract maximum concessions from developers for their constituents — however, it is this exact system that allows the councilmember to demand personal favors, or money, or both. The system of councilmember discretion in Los Angeles is not actually written into law. However, it still holds enough weight that councilmembers are comfortable with soliciting bribes, and developers are comfortable with paying up.

Monopoly

Compared to other cities with a “strong mayor” (i.e., the mayor has extensive powers over local administrations and the budget), Los Angeles’s mayor is relatively weak. Combined with zero at-large representation in Los Angeles’s city council (compared to, for example, Oakland) and the custom of councilmember discretion, this means that the councilmember alone has near total control over the fate of a housing development.

This is a crucial component — there is (almost) no countervailing power that a developer can point to in order to get their zoning change or general plan amendment project accepted. Since councilmembers hold discretion and they are the sole point of contact with regards to the development, this means they are able to extort the developers for far more than they might be comfortable with in a system with more countervailing forces.

Accountability (or lack thereof)

As I discussed in a previous post, housing is a (relatively) low salience issue. Of course, that’s changing, but it is still true that housing and housing-related activities require a lot of mental effort to understand that voters generally cannot spend much time on. This can be used for good, but it can also mean that councilmembers are able to get away with a lot more than they would otherwise.

Council races are generally low turnout — for example, Curren Price won his election with 8,000 votes in a council district with almost 250,000 people. This means that Price, or any councilmember for that matter, usually represents a council district they are not really beholden to. The odd year elections in Los Angeles before 2020 exacerbated this further — Jose Huizar and Mitchell Englander got ~13,000 votes in 2015, and Englander wasn’t even opposed.

While substantive voter accountability is lacking, media accountability has also been relatively lacking. Councilmember discretion is often taken at its word as a good thing, NIMBYism is often uncritically reported on, and, perhaps most importantly, voters don’t really care about it.

As an example, the Twitter user AaronGuhreen found in September of 2021 that Kevin de Leon was paid an unknown (but >$100,000) sum of money by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s subsidiary, the Healthy Housing Foundation, for consulting fees. (There is a long story behind the AIDS Healthcare Foundation that this post cannot possibly explain.) However, the Los Angeles Times only picked up on the story in March of 2023, despite all the information being publicly available.

What Happens Next

First, the corruption: Mitchell Englander’s former chief of staff, John Lee, is a current councilmember for the district Englander used to represent — and he has basically admitted to being “Staffer B,” who helped facilitate the bribery. It’s very possible that Lee will soon be implicated in a corruption probe, though I wouldn’t bet money on it happening particularly soon. Additionally, given the current structure of the council, I wouldn’t be surprised that some other story of discretionary approval and bribery solicitation appears sooner or later.

After the 2022 tape leaks (where councilmembers used racist and homophobic remarks while plotting to manipulate the redistricting process) and subsequent election, Nithya Raman put forward a proposal for charter reform to increase the size of Los Angeles city council, and state legislation has been proposed to create independent redistricting commissions in various cities.

However, given the glacial pace of government reform, I wouldn’t be so certain that charter reform will even happen, nor that it would be enough — for example, Chicago is infamous for its history of aldermanic privilege and associated corruption, and they have 50 seats (compared to the Los Angeles city council’s 15).

On the governance side, the primary solution is multiparty democracy, and the associated governing structures (such as proportional representation or multi-member districts) necessary to create it. On the legal side, councilmembers should liberalize land use (so as to avoid the possibility of opening themselves up to corruption during the zoning change process), and in the meantime, create clear and consistent guidelines for awarding zoning changes, as opposed to negotiating case-by-case.